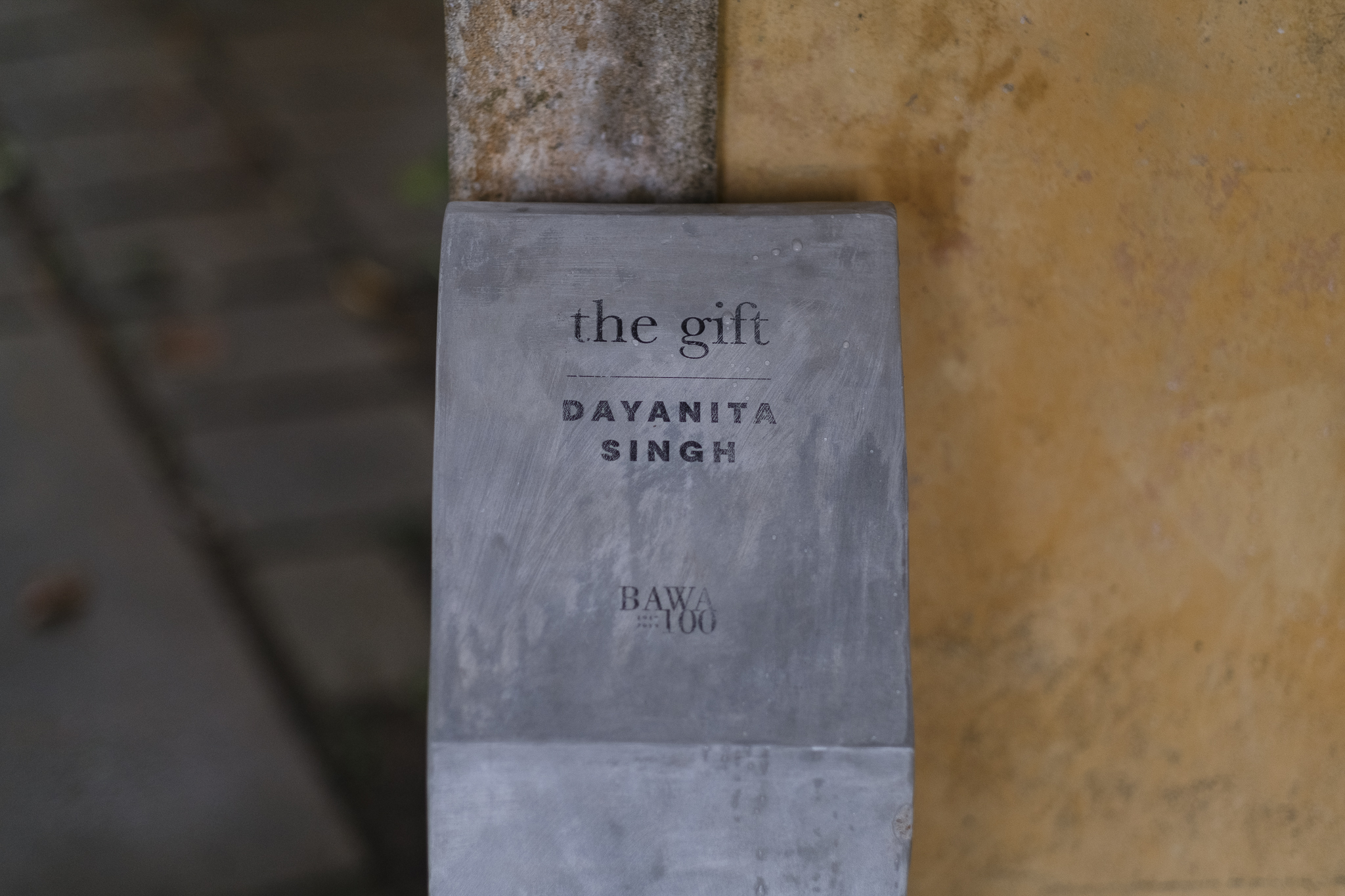

The Gift

“When we are moved by art we are grateful that the artist lived, grateful that he laboured in the service of his gifts. If a work of art is the emanation of its maker’s gift and if it is received by its audience as a gift, then is it, too, a gift?”

LEWIS HYDELunuganga was created by Geoffrey Bawa over a period of 40 years and is considered to be a seminal expression of his practice, a place where much of Bawa’s architectural thinking was explored and expressed through a series of built structures and the creation of a garden. Bawa always invited artists, including Laki Senananyake, Lidia Duchini, Fiona Hall, Jimmy Ong and Michael Ondaatje to make work on site or be inspired by it. Lunuganga has been and continues to be a quiet source of generosity for those interested to draw from this gift.

In his notable book on the subject of gifts, Lewis Hyde remarks “When we are moved by art we are grateful that the artist lived, grateful that he laboured in the service of his gifts. If a work of art is the emanation of its maker’s gift and if it is received by its audience as a gift, then is it, too, a gift?” These questions are key to how we perceive Lunuganga and how we continue to engage with it today. Hyde also speaks of gifts as agents of change, and we look to the garden which is both ever-changing and ever-constant as we reflect on the concepts of time and change.

In 2019, as part of the artistic programme commemorating Geoffrey Bawa’s 100th birthday, Lunuganga reconnected with this energy to host a programme of installations by artists and makers from Sri Lanka and abroad, in a series where the garden is explored as a site of hospitality and a place of encounter. Themes of nurture, shelter, labour, journey, generosity, perception and reflection offered each artist a unique opportunity to respond to the work of Bawa and his garden.

The artists invited for this project are: architect Kengo Kuma, artist Lee Mingwei, and Chandragupta Thenuwara and photographers Dayanita Singh and Dominic Sansoni. All five have had a long interest in the work of Bawa.

The centenary celebration offered the Trust a vehicle to bring to Sri Lanka a programme that positions Bawa’s work and the Trust’s mission within the wider contemporary discourse which spans across multiple regions and disciplines.

*

The Gift: Closing Conversation

29 August, 2021

*

The Gift: artist panel discussion

24 July 2019

*

The Gift: Closing Conversation

29 August, 2021

*

The Gift: artist panel discussion

24 July 2019

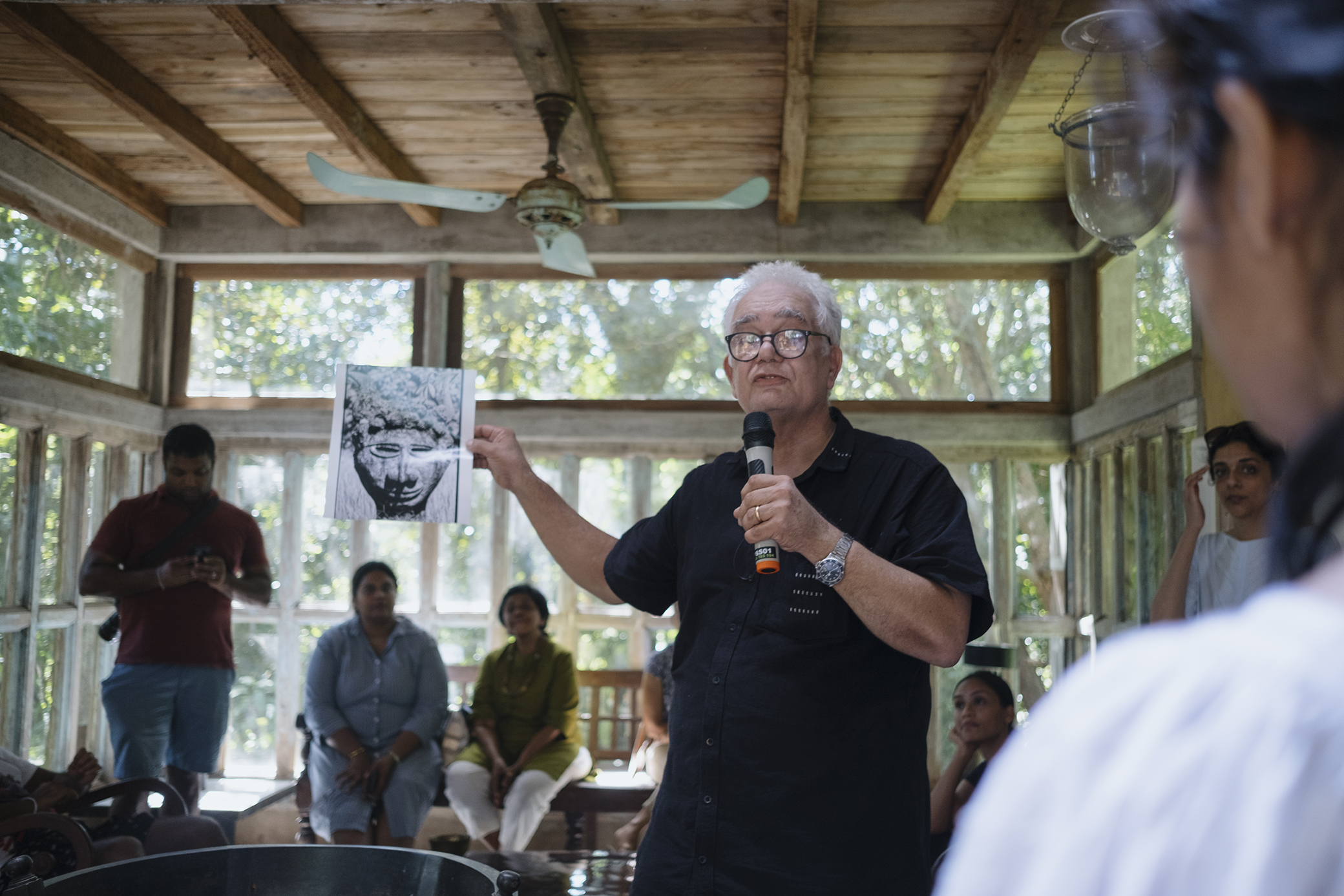

Panel Discussion featuring the participating Artists Dominic Sansoni, Lee Mingwei, Chandragupta Thenuwara and Dayanita Singh

Moderated by:

Suhanya Raffel, Executive Director of M+, Hong Kong, and Trustee, Geoffrey Bawa & Lunuganga Trusts

Sean Anderson, Associate Curator of Architecture & Design, MoMA, New York

Shayari de Silva, Curator, Lunuganga Trust

*

The first launch of The Gift installation Series

5 January 2020

5 January 2020

Kithul-Ami

Kengo Kuma

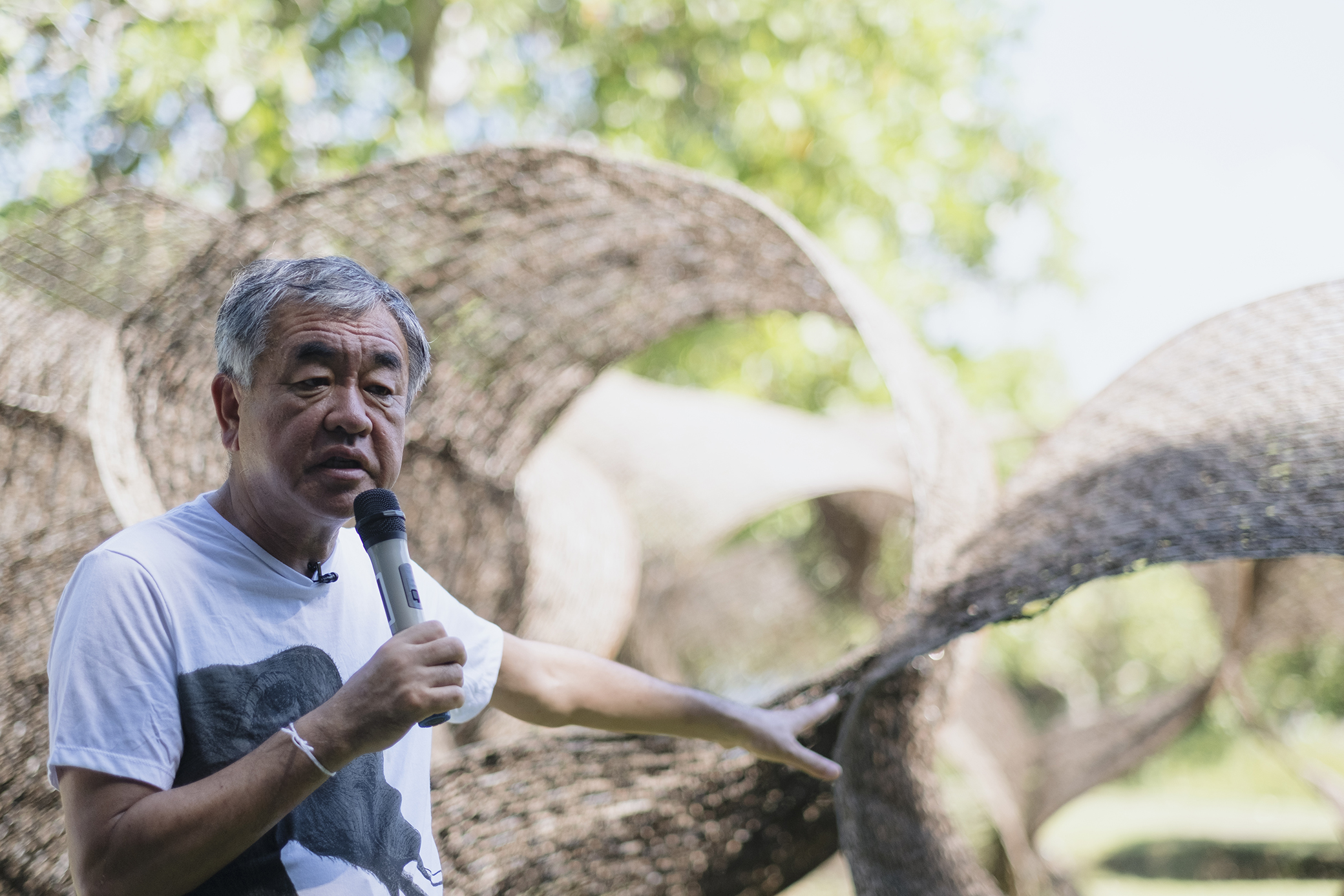

Kengo Kuma’s practice has been characterized by a commitment to using traditional materials and crafts in innovative forms and techniques. Pavilions have also played an essential role in processes of experimentation and development of ideas, in Kuma’s architecture practice as within the discipline. For this work at Lunuganga, Kuma drew inspiration from the outdoor furniture Bawa designed for Kandalama, a few of which are scattered across the garden, and the local kithul craft, where strands from the kithul flower are dried and woven into household objects. Working with a team shepherded by Disna Shiromali, a weaver based in Galle, and Indika Kumarasingha, a metalsmith based in Bentota, the pavilion was designed to offer a brief moment of repose and reflection through the framing of views. The pavilion can also be used for tea ceremonies and similar gatherings.

Kengo Kuma

Kengo Kuma’s practice has been characterized by a commitment to using traditional materials and crafts in innovative forms and techniques. Pavilions have also played an essential role in processes of experimentation and development of ideas, in Kuma’s architecture practice as within the discipline. For this work at Lunuganga, Kuma drew inspiration from the outdoor furniture Bawa designed for Kandalama, a few of which are scattered across the garden, and the local kithul craft, where strands from the kithul flower are dried and woven into household objects. Working with a team shepherded by Disna Shiromali, a weaver based in Galle, and Indika Kumarasingha, a metalsmith based in Bentota, the pavilion was designed to offer a brief moment of repose and reflection through the framing of views. The pavilion can also be used for tea ceremonies and similar gatherings.

Zephyrus’ Breath

Lee Mingwei

Lee Mingwei creates participatory works which explore issues of trust and intimacy often through the lens of time and chance. Mingwei’s installation at Lunuganga draws from a tripartite work titled Trilogy of Sounds done in 2010 for Mount Stuart in the Isle of Bute, Scotland. In bringing the bells to Sri Lanka, several subtle adjustments were made by the artist to adapt to the local context. Here, they are made of three dimensions of locally available pre-cast brass tubes, suggesting a timbre akin to the temple bells of the island. Bawa himself used fourteen different bells throughout Lunuganga — each bell having a distinct register which helped identify his location in the garden. This work, titled Zephyrus’ Breath, reveals the sensitivity to place and encounter which characterizes much of Mingwei’s work, offering an experience that is unique to each visitor.

Lee Mingwei

Lee Mingwei creates participatory works which explore issues of trust and intimacy often through the lens of time and chance. Mingwei’s installation at Lunuganga draws from a tripartite work titled Trilogy of Sounds done in 2010 for Mount Stuart in the Isle of Bute, Scotland. In bringing the bells to Sri Lanka, several subtle adjustments were made by the artist to adapt to the local context. Here, they are made of three dimensions of locally available pre-cast brass tubes, suggesting a timbre akin to the temple bells of the island. Bawa himself used fourteen different bells throughout Lunuganga — each bell having a distinct register which helped identify his location in the garden. This work, titled Zephyrus’ Breath, reveals the sensitivity to place and encounter which characterizes much of Mingwei’s work, offering an experience that is unique to each visitor.

Symbiotic Organisms

Dominic Sansoni

Dominic Sansoni has been photographing Lunuganga since 1977. Perhaps the most well known images are those which he took along with Christoph Bon, in black and white, for Bawa’s own publication Lunuganga in 1989. For his work in The Gift, Dominic took a very close look at the garden, showing the garden at a scale that is rarely observed. This “garden within a larger garden” which Dominic has photographed reflects many of the themes that have characterized his practice over the years; an interest in chroma, or the qualities of colour, landscapes and things observed as they are naturally found to be. Viewed together, the photographs in this installation show Dominic’s acute observations of the changing and unchanging elements in the garden, and the relationships that he has documented over the years.

Dominic Sansoni

Dominic Sansoni has been photographing Lunuganga since 1977. Perhaps the most well known images are those which he took along with Christoph Bon, in black and white, for Bawa’s own publication Lunuganga in 1989. For his work in The Gift, Dominic took a very close look at the garden, showing the garden at a scale that is rarely observed. This “garden within a larger garden” which Dominic has photographed reflects many of the themes that have characterized his practice over the years; an interest in chroma, or the qualities of colour, landscapes and things observed as they are naturally found to be. Viewed together, the photographs in this installation show Dominic’s acute observations of the changing and unchanging elements in the garden, and the relationships that he has documented over the years.

*

Public opening of Chandragupta Thenuwara & Dayanita Singh

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Public opening of Chandragupta Thenuwara & Dayanita Singh

6 September 2020

Lunuganga Chairs

Dayanita Singh

Dayanita Singh uses photography to reflect on spaces and experiences; often capturing the ephemeral, transcendent qualities inherent in architecture. Her images are intended to be encountered through fluid sequences and are housed in architecture designed by the artist to encourage the viewer to engage keenly; subtle changes over time may be observed by the astute viewer. Her work for The Gift follows an extensive body of work on Bawa. With this installation, the artist states, “Somehow — alongside my interest in architectural structures, came the clarity about the limitations of the photographic print. Box 507 emerged precisely because the photographs revealed too much and not enough at the same time. As though a photograph could not get to the essence of what I experienced in the sublime Kandalama. Similarly, when I printed the Lunuganga Chairs — they seemed almost vulgar in how much detail they revealed. There was too much information — and then, by chance, the painting started. I no longer wanted the dark blacks or the highlights — just if I stayed in the mid tones, maybe something more would reveal itself. Perhaps closer to my experience of the place.”

Dayanita Singh

Dayanita Singh uses photography to reflect on spaces and experiences; often capturing the ephemeral, transcendent qualities inherent in architecture. Her images are intended to be encountered through fluid sequences and are housed in architecture designed by the artist to encourage the viewer to engage keenly; subtle changes over time may be observed by the astute viewer. Her work for The Gift follows an extensive body of work on Bawa. With this installation, the artist states, “Somehow — alongside my interest in architectural structures, came the clarity about the limitations of the photographic print. Box 507 emerged precisely because the photographs revealed too much and not enough at the same time. As though a photograph could not get to the essence of what I experienced in the sublime Kandalama. Similarly, when I printed the Lunuganga Chairs — they seemed almost vulgar in how much detail they revealed. There was too much information — and then, by chance, the painting started. I no longer wanted the dark blacks or the highlights — just if I stayed in the mid tones, maybe something more would reveal itself. Perhaps closer to my experience of the place.”

In conversation with Dayanita Singh

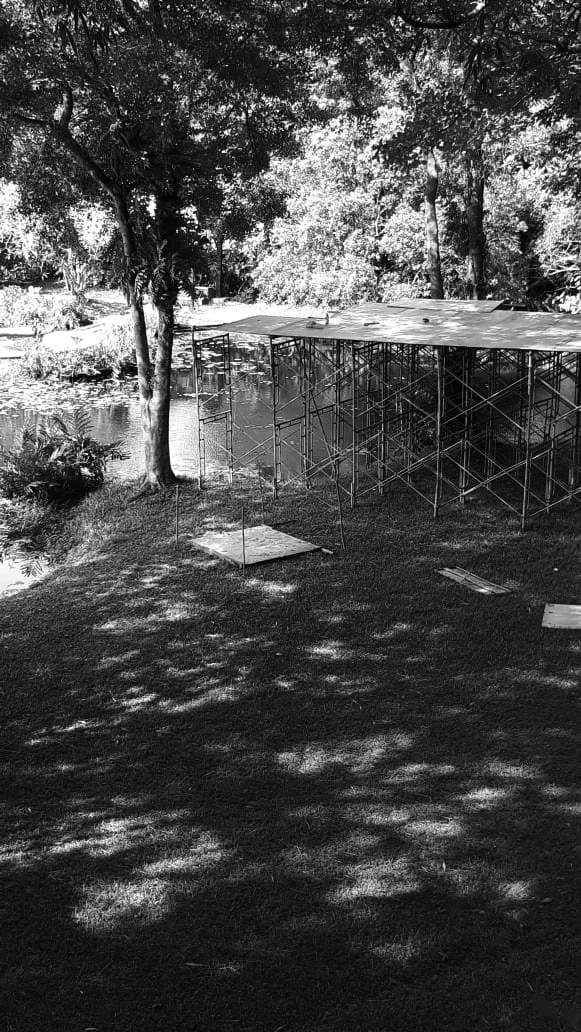

Beautification II

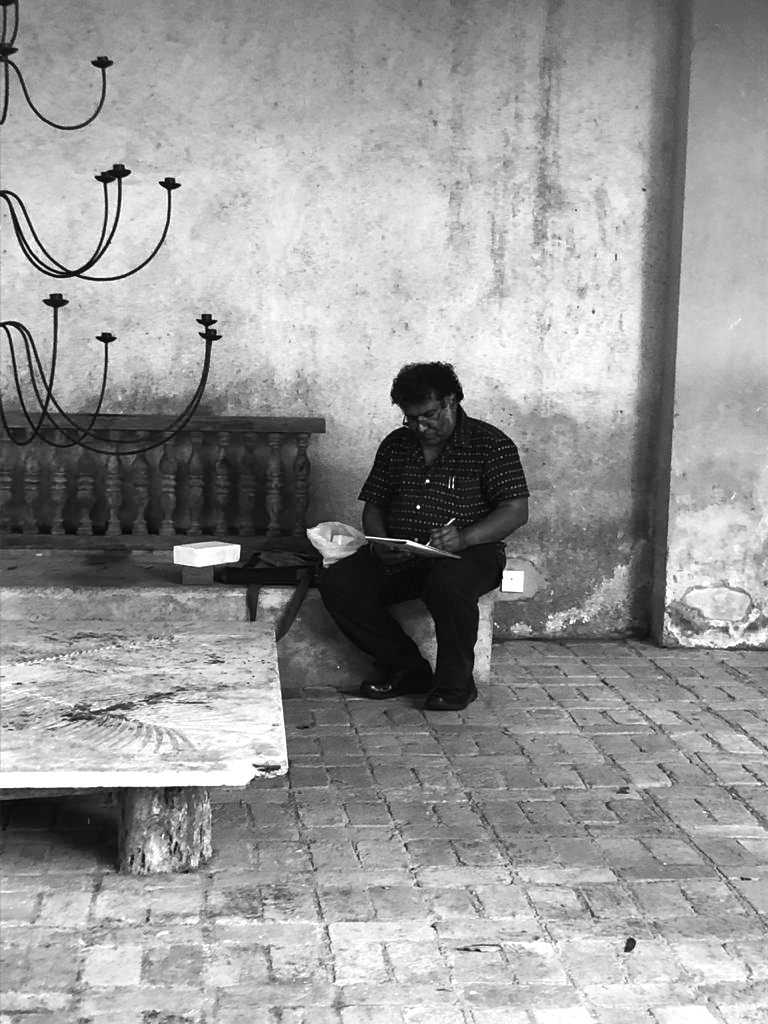

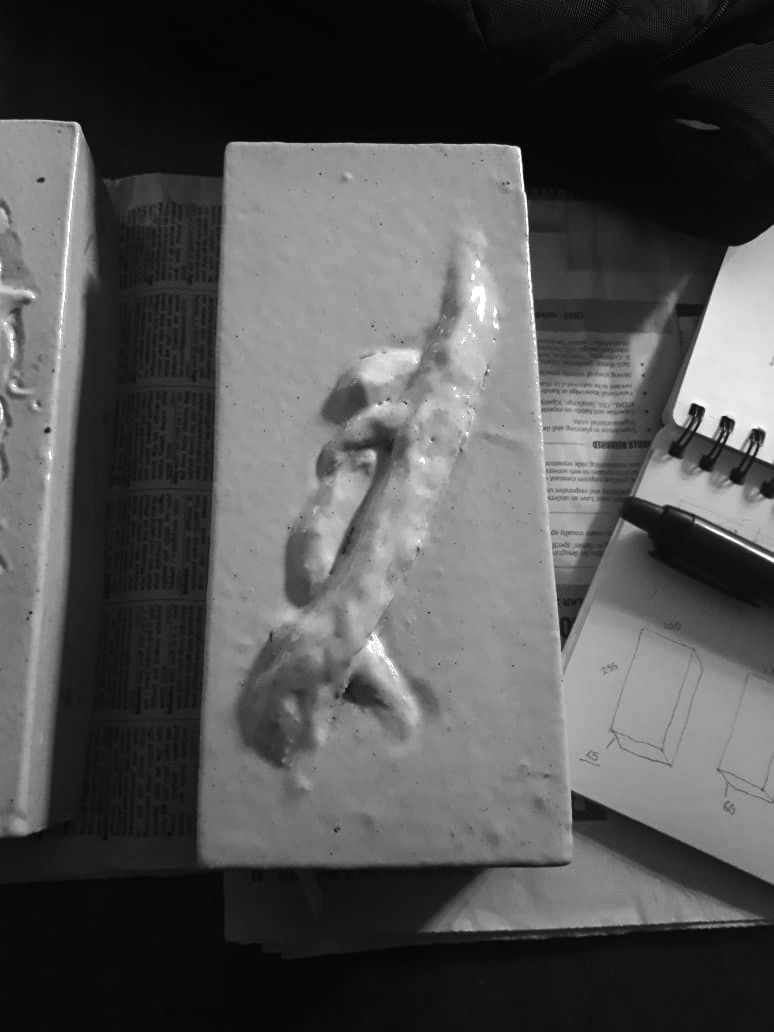

Chandragupta Thenuwara

Chandragupta Thenuwara’s practice as an artist is deeply intertwined with the politics of Sri Lanka. Formally trained in painting, Thenuwara works in a range of media and uses intricate details tinged with dry humour to critique the ever-unfolding political landscape of the island. Thenuwara’s work at Lunuganga once more picks up the theme of Beautification, the subject of his solo exhibition in Colombo in 2013, which addressed the then-government’s urban gentrification programme through the guise of ‘Beautification.’ In this new work, Thenuwara engages with the garden through the existing natural and man-made elements and Bawa’s own practice of using systems of grids and axes to ground his work, which then negotiates the extant natural landscape. Beautification, too?

Chandragupta Thenuwara

Chandragupta Thenuwara’s practice as an artist is deeply intertwined with the politics of Sri Lanka. Formally trained in painting, Thenuwara works in a range of media and uses intricate details tinged with dry humour to critique the ever-unfolding political landscape of the island. Thenuwara’s work at Lunuganga once more picks up the theme of Beautification, the subject of his solo exhibition in Colombo in 2013, which addressed the then-government’s urban gentrification programme through the guise of ‘Beautification.’ In this new work, Thenuwara engages with the garden through the existing natural and man-made elements and Bawa’s own practice of using systems of grids and axes to ground his work, which then negotiates the extant natural landscape. Beautification, too?

*

Behind the Scenes